Even so, risk experts say some safety laws just aren’t worth it.

Peter Passell

You’ve watched in horror a dozen times: Scenes of barely recognizable aircraft parts strewn across smoldering moonscapes, with the occasional shoe or child’s toy the only reminders of lives snuffed out in unimaginable terror. And no doubt you’ve wondered when it would be your turn, a thought quickly shrugged away but never truly forgotten.

Flying, everyone knows, is a risky business. Any expense that makes it safer thus seems an expense worth making. And the only question most people ask after a crash is how to get the regulators to get off their duffs before the next one.

But the truth comes in shades of gray, not black and white. Americans’ obsession with the tiny probability of dying in an airline accident is, at best, a distraction from the reality that commercial aviation is one of the great blessings of the age. At worst, it is an invitation to expensive and even self-defeating fixes, a symptom of our inability to cope sensibly with risk. But Republican conservatives in Congress are now pressing for a more sharp-penciled analysis of the cost of government health and safety regulations.

Just how safe is flying in America? Based on the experience of the last two decades, Arnold Barnett, a management professor at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, sets the probability of dying from unnatural causes on your next commercial jet flight at about one in seven million. A flier who boards a jet each day can thus expect to meet the grim reaper every 19,000 years.

The propeller planes linking hundreds of small cities to big airports are three or four times as dangerous. But that only brings the odds of ending up a grim statistic to one in two million. The chance of suffering a heart attack while waiting for the conveyor belt to mangle your luggage is much greater.

The yawning gap between the actual and imagined risk of flying no longer surprises specialists in risk analysis, who make careers of explaining why people who brush aside the dangers of driving on icy highways or gorging on cookie dough ice cream are so ready to believe that portable phones cause brain cancer. But a comparison of the way risk analysts think about safety with the way Government balances risk against potential gain is sobering.

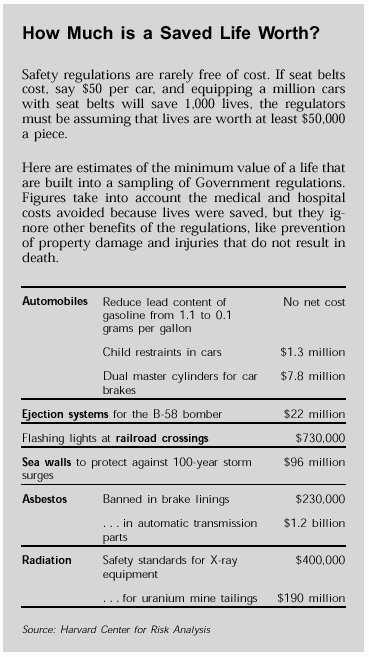

Probabilities alone don’t offer much insight into which chances are worth taking. That question, suggests the brave new science of risk analysis, can be answered only by weighing the cost of avoiding a statistical death against the subjective value of life.

Try that one again. Assume for the sake of argument that it would cost $500 per car to put anti-skid brakes in each of the 10 million cars sold this year--a total of $5 billion. Assume that installing the gadgets on this year’s fleet would ultimately save 5,000 lives, or $1 million per life. Assume that, on average, people value their lives at up to $5 million. Since the $1 million cost of saving a life is less than the $5 million value of life, the safety feature must be worth buying.

Sounds O.K., at least until the part about the value of life being $5 million. Who is to say that a life is worth $5 million rather than $500 million?

One answer is Americans couldn’t afford to spend $500 million. Kip Viscusi, an economist at Duke University, estimates that if the entire gross national product were devoted to making life safer, there would only by $55 million available to prevent each accidental death. So, at least in this limited sense, life must be worth less than $55 million.

More to the point, people voluntarily accept the risk of death in return for money all the time. Dozens of studies have imputed a value to life from data on the extra wages required to lure workers to perform dangerous jobs. If, for example, it takes an extra $100,000 in lifetime earnings to persuade miners to cope with one extra chance in a hundred of premature death underground, miners must implicitly value their lives at no more than 100 times $100,000 or $10 million.

Dozens of other studies have focused on the cost of safety devices that are voluntarily purchased in order to assay how much people are willing to spend to reduce the probability of accidental death. If smoke detectors cost $20 and are widely seen as reducing the risk of a fiery death by one chance in 10,000, buyers must value their lives at at least 20 times 10,000, or $200,000.

These studies hardly produce uniform answers--nor do risk analysts expect them to. After all, people have very different “tastes” for risk. But researchers are still willing to generalize. Most middle-income Americans, they say, usually act as if their lives are worth $3 million to $5 million based on what they demand in extra pay for dangerous jobs and what they spend for safety devices.

A few Federal agencies, notably the Department of Transportation, evaluate new health and safety regulations by comparing an estimate of the cost per life that would probably be saved against a benchmark figure. But most are too savvy to be caught putting a value on life. And in some cases, the law actually bars consideration of cost in deciding how safe is safe enough.

The result is a hodgepodge of cost-effective regulations mixed with inconceivably expensive ones. At one extreme are rules that actually save money as well as lives. Mandatory childhood immunization programs, for example, cost less than treating the diseases. At the other extreme are rules that probably save only a statistical fraction of a life, and at enormous cost. Strict controls on benzene emissions by the tire makers run to an estimated $340 billion per life spared.

The most wasteful rules, however, are the ones that do save dozens of lives but at farcical cost. Draconian controls on toxic wastes from a variety of manufacturing plants, as well as cleanup standards for abandoned uranium mines and chemical waste sites, fit the category. Indeed, with cleanup obligations on the books that would cost government and industry several hundred billion dollars to meet over the next decade, risk researchers argue that the net impact of the programs on life expectancy may actually be perverse.

How so? The affluent live longer than the poor, at least in part because they have the will and the means to lead more secure lives. Not only are they more likely to visit a doctor before a cough turns into pneumonia, they can afford fresh vegetables, health clubs and bicycle helmets for their kids.

Hence the life-lengthening effects of requiring auto makers to install anti-skid brakes or preventing trace chemicals from ending up in drinking water must be weighed against the life-shortening effects of reducing living standards in order to pay the bill.

Mr. Viscusi estimates that the break-even point in what specialists have dubbed “risk-risk” calculations is around $10 million. Thus by his reckoning, regulations that reduce private spending by more than $10 million per statistical life saved are probably self-defeating.

Where does airline safety fit in this picture? When pressed to mandate life-preserving technology for commercial aircraft, the Federal Aviation Agency has generally acted with one eye on the economics. According to a 1984 study, smoke detectors required in airplane lavatories save lives for about a half-million dollars each. Emergency floor lighting runs to approximately $1 million per life saved--well under the $3 million to $5 million benchmark for the value of life. Still, some of the most hotly debated proposals suggest just how seductive bad ideas can be.

Infants can’t use ordinary seat belts, so they are more vulnerable than adults in survivable airplane accidents unless they are strapped into special child seats. But there is a big catch here: Airlines insist that parents buy tickets for children if kids are to be assured seats of their own. So if Washington had demanded child restraints in response to petitions from safety groups in the 1980’s, an estimated one-fifth of the infants who now fly in relative safety would be priced out of the air and end up traveling at greater risk in autos. On balance, more lives would be lost in cars than saved in planes.

A parallel question--one hardly ever asked--is whether aircraft manufacturers voluntarily spend too much on safety. If free markets worked according to Hoyle, one might expect Boeing and Airbus to sell less-safe planes, were it profitable to do so. But since aircraft makers and airlines--not to mention product liability lawyers--are deeply reluctant to acknowledge that there is any acceptable trade-off between cost and safety, such calculations are apparently never made in any systematic way.

What is apparent, though, is that commercial aviation is now so safe and the system that keeps it safe is so complex that the rare fatal accident offers little insight into how flying could be made safer at reasonable cost. Take the case of USAir and its subsidiaries, which suffered seven deadly accidents in seven years--a frequency of mishaps that Mr. Barnett of M.I.T. calculates had only a 2 percent probability of being purely coincidental. Add the fact that USAir was apparently guilty of an embarrassing number of safety and training miscues, including the failure to refuel a plane before takeoff, and it is understandable why many travelers are looking for other ways to get to Pittsburgh.

But like the clusters of rare cancers that occasionally make headlines, clusters of airline accidents are harder to interpret than it might at first seem. Much depends on how the universe of possible coincidences is defined. For while the probability that chance alone generated USAirs unenviable safety record was just 1 in 50, there was a probability of 1 in 8 that some major airline that was no more dangerous than its competitors would crack up seven planes in seven years. One in 8 is still daunting odds, but not quite a smoking gun.

Even if one concedes that USAir must have been doing something disastrously wrong, it is hard to pinpoint what it was doing disastrously wrong. While it is gratifying to see that USAir pilots are now on notice to double-check fuel gauges before take-off, it is far from clear that the carrier’s safety lapses were more serious than those of competitors with spotless accident records.

Safe air travel is worth some money and trouble, of course. And, no doubt, the tens of thousands of people who earn their paychecks keeping it safe will come up with some affordable ideas on how to make it safer. But the fact that many Americans who can’t spot the difference between a wart and a melanoma know all about aircraft de-icing techniques and Doppler radar says more about their fears than about their knowledge of risk.