April 2018

Working on writing

Madelyn Voelker, graduate student

1 April 2018

During winter quarter I had the opportunity to take a course from Dr. Sylvia Yang at Shannon Point. This was a very productive and rewarding experience. If you ever get the chance to take a class from Sylvia I highly recommend it! This particular course was focused on learning and refining the manuscript and thesis writing process. We examined scientific writing from the big picture down to the little picture. For example, we talked about techniques for productive a writing environment, the typical frame work of each section of a scientific paper, and proper sentence structure. As this was such a useful experience for me I wanted to highlight a few things I learned.

One big take away was that it is the writers job to present the information as clearly as possible. If a reader is confused, it is the problem of the writer to fix it, not the reader to better their comprehension skills. Another broad take way was an understanding and appreciation for the difference between writing and editing. This understanding helps me to produce because I am encouraged to just get something on paper, because I KNOW it will be edited and improved. Writing is never perfect the first time – that is why editing is a thing. BUT for editing to happen there needs to be something on the paper.

Another thing I gained from this class was acceptance of what I need to be productive. I used to be in denial about my ability to focus. I wanted to believe that I was good at tuning out distractions, however, this is NOT the case. I need a quiet and consistent environment. Even people coming and going can break my focus. I have found that it takes me a while to get focused, but once I am, I can go for a long time. The trick is to get myself in a place where there aren’t a lot of things to break my focus AND to give myself enough time to get focused in the first place. In summary, it is important for any writer to be honest with themselves about what they need to produce.

Lastly, I didn’t realize there was an actual formula for writing in a clear style (and books that walk you through it! I’ve listed one we used below). One very intuitive and easy to remember technique we learned was to put new and complex ideas at the ends of sentences and paragraphs. Adhering to that concept is a strait forward way to increase the quality of scientific writing. It doesn’t require great literary skills to accomplish, just careful reading (and re-reading) of what you wrote to identify the issue. After that it usually only takes flipping around a sentence or two to accomplish.

I still have a long way to go in producing a finished thesis but this class has helped me get a good start. The process is daunting but I now feel like I have a good set of tools to deal with it. Hopefully you will be able to see what all my new tools can do when I finish my thesis in a few(ish) months!

A useful book on writing:

Style: Lessons in clarity and grace by Bizup and Williams

Processing data

MacKenna Nemmarch, undergraduate student

1 April 2018

This month I began cleaning up our behavioral data for analysis, which has been a very exciting process. To review, there are five behaviors I am looking for that research has reported are indicative of active hunting (See March post for further information). These behaviors are:

- Upside-down/belly-up to get a better view underwater

- Scanning/rapid movement on bankside

- Rapid movement or a visible wake in middle portion of the creek

- Jumping out of water

- Consistent surfacing in the narrow region where salmon travel up the fish ladder or further up the creek - ‘parking’ (I may split this behavior into another region where fishermen are casting their lines as this has been specified in many data points. This is meaningful because harbor seals grab fish hooked by fisherman. A pretty ingenious method if you ask me.)

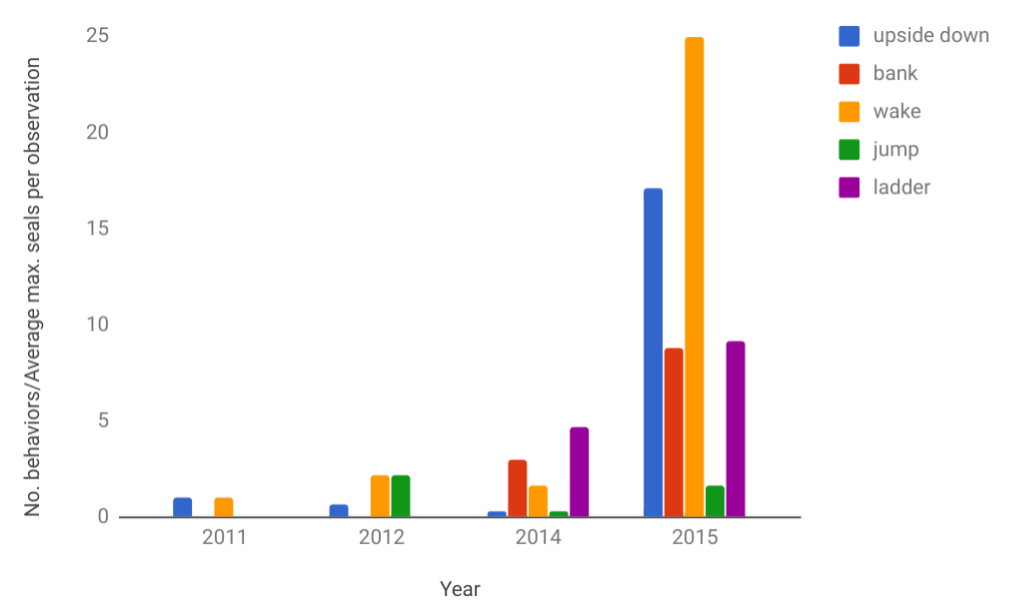

I am beginning to notice many patterns, like some seals specializing in a particular behavior more frequently than others, either resulting in more or no difference in success. Some behaviors are also displayed by all seals more often than others. To make this a bit more meaningful, I’ve created a figure to represent the behavioral data I’ve sorted through up to 2015. Data from 2013 are omitted due to lack of behavioral record.

Fig 1. Number of behaviors witnessed during observations relative to average maximum number of seals per observation.

Wake/rapid movement appears to dominate most years with ‘parking&rsquo becoming more common as time progresses. It is also apparent that the seals are diversifying their behavior, which started with upside down and rapid movement and has grown to include several others. I would be interested to see how this compares to the number of salmon that return to the hatchery. Since salmon are the cause of such behaviors, I predict that as returns lower, seals learn to use other behaviors in attempt of higher success. Seals may additionally flock to the fish ladder/area where fishermen cast their lines if they are finding it to be easier/have greater success there compared to previously used methods, which we can see is becoming increasingly common.

Interestingly, I am finding that there are a few seals who tend to be successful at hunting without displaying a behavior of any type (seal 38, 108, 109). It will be compelling to see how their success rates compare to individuals like 12 who hunt on the bankside more frequently and successfully than other behaviors. Here is a neat photo of seal 12 doing just that. This specific event lead to a successful catch. You can see the salmon in the lower left:

Harbor seal hunting salmon at Whatcom Creek in Bellingham, Washington State, USA. Photo by R. Wachtendonk.

Next on the agenda is to finish sorting through 2016 and 2017 and looking at whether each behavior observed resulted in a successful catch. Currently, it is looking like bankside and fish ladder hunting has the highest success (20% and 30% success respectively). Alternatively, I can compare a seal’s known success rate with the number of times they evidence various behaviors. Our behavioral data are only tied to individuals up to 2015, so this will require a significant amount of identification. My goal is to have all of this complete by the next blog post - I cannot wait to share what I find! Scholars' Week is sure coming up quick…

Marine mammal bycatch

Alisa Aist, undergraduate student

2 April 2018

There are many threats to marine mammals. Some of these threats have been greatly reduced in the United States by the Marine Mammal Protection Act and other legislation. However, there are still many marine mammals being harmed by human activities. Bycatch from the fishing industry is a huge problem for marine mammals and other organisms. Marine mammals have a life strategy that is particularly susceptible to extinction from intense hunting pressures on older individuals (Lewison, 2004). There are many challenges to understanding the effects of bycatch. One is that it is difficult to know how much bycatch there is, inaccurate reports are common to avoid punishment. Another is that ecological consequences are likely very complicated and there are higher order not just species-specific effects (Lewison, 2004). From 1990 to 1999 there was a decrease in bycatch (NOAA, 2017) and further technological improvements and harsher penalties have leading the trend to continue. Roughly half of those caught are cetaceans and the other half are pinnipeds.

People are working towards reducing bycatch of marine mammals and other organisms. The key is understanding why the animals are getting caught to begin with. Only by understanding how a porpoise gets caught we can find a way to solve the problem (Larsen et al., 2007). To reach this level of understanding there need.s to be a lot more research into the behaviors of marine mammals in the wild. At present it is believed that it is often healthy animals in small groups that have a spatial and temporal overlap with the vessels around a concentrated food source. The nets also create a new niche for organisms to use (Zollett, 2018). To try and keep marine mammals out of nets they try using exclusion and acoustic devices, however, they can be expensive and other conditions may make them totally ineffective and neither are effective without any other interference (Zollett, 2018).

The longline fishery is one of the fisheries where bycatch has been studied. Werner et. al. (2015) explored many of the current methods for reducing bycatch for longlines, they also suggest that each method is evaluated for three checks, that it “works for bycaught species, work fishers, and have negligible or manageable unintended consequences”. The consensus from all the articles I read was that more research on the behaviors of marine mammals to develop effective methods for reducing marine mammal bycatch.

References

- Larsen, F., Eigaard, F. & Tougaard, J. (2007). Reduction of harbour porpoise (Phocoena phocoena) bycatch by iron-oxide gillnets. Fisheries Research, 85, 270-278.

- Lewison, R. L., Crowder, L. B., Read, A. J., & Freeman, S. A. (2004). Understanding impacts of fisheries bycatch on marine megafauna. Trends in Ecology & Evolution, 19, 598-604.

- NOAA. (2017). Marine Mammal Stock Assessments. NOAA Fisheries. www.nmfs.noaa.gov/pr/sars/ Accessed April 1, 2018.

- Werner, T., Northridge, S., McClellan Press, K., & Young, N. (2015). Mitigating bycatch and depredation of marine mammals in longline fisheries. ICES Journal of Marine Science, 72, 1576-1586.

- Zollett, E. (2005). A Review of Cetacean Bycatch in Trawl Fisheries. Literature review prepared for the Northeast Fisheries Science Center. www.nefsc.noaa.gov/publications/reports/EN133F04SE1048.pdf Accessed April 1, 2018.