January 2016

New members and new direction

Raven Benko, undergraduate student

29 January 2016

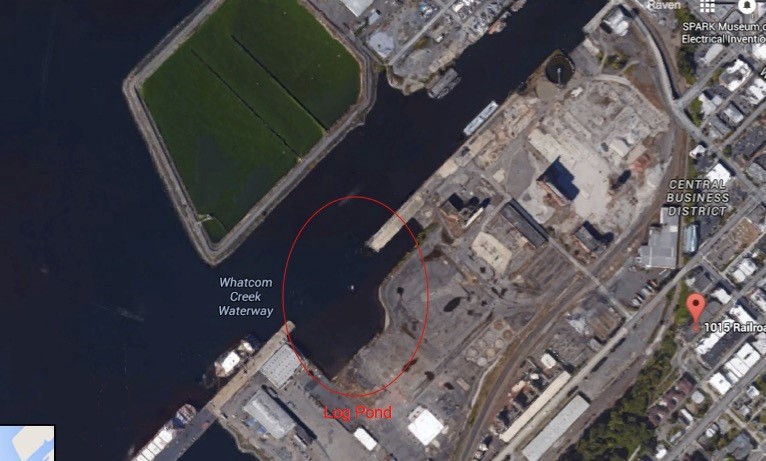

Greetings seal enthusiasts! I wanted to briefly introduce myself and provide an update on the Bellingham Bay harbor seal population study as the first month of the new year comes to a close. If you are new to the blog or this study, we are focused on a population of harbor seals historically found in a secluded “log pond” at the mouth of the Whatcom Creek Waterway (see map below). This inlet has been an extremely useful habitat for harbor seals (Phoca vitulina) as it is relatively secluded, has little boat or pedestrian traffic, is close to a popular feeding ground, and has had (up until September of 2015) floating log booms on which the seals could rest and rear their young. We chose this site as a study area once the plan for a large construction project which would repurpose the abandoned industrial lot became known. The Port and City of Bellingham plan to construct a new waterfront district in the area, equip with a shoreline park, housing and business sectors, and a marina (click for more information). Our main goal is to monitor the long term response of the harbor seal population to anthropogenic disturbance as the project progresses and reaches completion. We have population counts starting in 2007 before the Waterfront District Project began and continued through to today.

Photo by google Earth, January 18, 2016

I started working on this project in June of 2015, was able to experience the joyous summer breeding months, and was present for the removal of the log booms as the construction intensity began to increase. Our team has changed around a bit, and I will now be acting as manager for this project, working closely with a few new and old members to continue making improvements and monitoring the seal situation down in Bellingham Bay. I am in my third year at Western Washington University studying marine biology and environmental policy and I am extremely excited about what this project means ecologically and politically. Two new members have also joined the team: Virginia O’Callahan, a third year student studying ecology, evolution, and organismal Biology, and Alisa Aist, a first year student also studying marine biology and environmental policy. Our last member, Holden Miller, has been a part of the project for over six months.

As the construction continued to increase, I started to wonder which vehicles, noises, vibrations, etc. were the most distasteful to our seal population and would deter them from visiting the log pond. To address this question, our team is now exploring the possibility of creating a “Snapshot Disturbance Index” which theoretically would work a lot like a habitat index for all of us ecologically-minded folks. However, our index would be able to provide us with a quantitative evaluation of the degree of disturbance (i.e. noise pollution, boat traffic, pedestrian proximity, water quality, and other variables) at a specific observation time, ideally allowing us to see if certain types of construction have more of an immediate affect on population numbers than others. The image below gives an insight in to the kinds of construction that is currently occurring.

Photo by R. Benko

All of the construction occurs well within the Waterfront District Plan specifications, and we have not seen any evidence that it poses a threat to individual seals. The construction plans include beneficial waste removal and habitat conservation efforts for the marine environment as well. We are continually grateful to Alan Birdsall and the Port of Bellingham for allowing us to observe these interesting interactions between harbor seals and humans!

More news on the future of the harbor seal population and the progress of the project to come in February.

Management and conservation implications of studying harbor seal foraging behavior

Daniel Woodrich, undergraduate student

26 January 2016

Our observations at Whatcom Creek allow us to identify individual differences in occurrence and hunting strategy, such as the inverted seal from the December blog. Why is it important to identify these differences? It turns out that it is one of the most important analyses we can make, as it is a matter of life and death for certain harbor seals that compete with humans for commercially viable fish in our local ecosystem and worldwide.

By 1970, harbor seals populations plummeted to between 2,000 and 3,000 individuals due to human killings in the Pacific Northwest, which were instigated by state-sponsored bounty programs that were designed to increase the number of fish available to fishers by removing this competing species. Since the federal MMPA (Marine Mammal Protection Act) passed in 1972, making their killing illegal, harbor seal populationshad risen by the 1990s to 10x that of the 1970s, and have since leveled off at near 30,000 seals. However, tensions remain and reports of illegal killings of harbor seals still are reported in the region. Harbor seals are not considered the largest problem at the Bonneville Dam on the Colombia River, it is California sea lions camping at the area for salmonids that have been targeted for legal culling (killing) by the ODFW since 2012.

California sea lion in the

Bonneville

Dam fish ladder.

Photo by Rick Bower/AP/Via KPLU.org

Another region of the world where harbor seals have been targeted due to competition with human fishers is the Moray Firth, Scotland. UK’s Conservation of Seals Act 1970 (CoSA) has permitted fishers to legally shoot seals with very limited restrictions. In the last decade new efforts have been launched to set standards for where seals may be culled, as well as to try to better quantify how many seals are being culled and yearly limits. In 2005, the first year of the new management plan, 46 harbor seals were reported to have been legally culled. There has been much recent research in the region to investigate both the idea of individual ‘rogue’ or ‘problem’ seals (seals that disproportionally harm fish stocks) and the effectiveness of removal on the health of fish stocks.

Harbor seal in the Moray Firth

Photo from gaelholidayshome.co.uk

Given these very real threats to harbor seals, and the fish species on which they prey, it is important to better understand how to appropriately identify any/which seals are causing the most problems, and if removing these seals will help fish populations rise in the long term. Not knowing which seal is a potential problematic seal means risking giving a seal a non-deserved death sentence: certainly an ethical faux-pas. Indiscriminately removing seals without tracking the effects on fish populations is just as irresponsible, because generalist predators like harbor seals can have complicated ecological effects on species below their trophic level.

We seek to use our study system as a model for how to identify potentially problematic seals. Past research has found that certain individual seals appear more often in the creek, but that there are mostly new seals in the creek every year. We do not know if any of these seals are actually problematic seals from the point of view of fisheries. However, if that were to be the case our results suggest that removal in our study area could have an effect only over a short timescale, but possibly not over a long one because it is possible that removing a problematic seal would simply result in a new seal taking its place shortly thereafter. Identifying individual variations in seal occurrence in the creek and foraging behavior is a helpful step towards the management and conservation of harbor seals in these systems.