September 2017

Sex determination

Madelyn Voelker, graduate student

1 September 2017

I have recently completed sex determination analysis on the samples from Baby Island, Whidbey Island Basin. The protocol used was developed by Matejusová et al. (2013). They used a positive control that I did not have access to, so to make my results more defensible I relied on repetition and cycle threshold (ct) values. For assigning females I required each sample to have two consistent positive amplifications (below 40 ct) for the X chromosome marker, and two consistent negative amplifications for the Y chromosome marker. For assigning males I required each sample to have two consistent positive amplifications (below 40 ct) for both the X and Y chromosome markers. With these parameters, a total of 133 out of 248 samples where successfully assigned a sex. This result translates to a 54% success rate. This success rate is lower than previous studies have documented, which have obtained above a 70% success rate (Matejusová et al. 2013, Rothstein 2015), but I’ll take it!

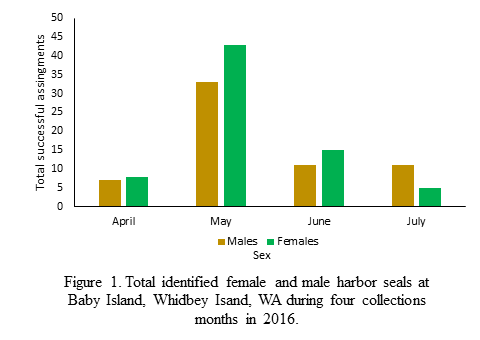

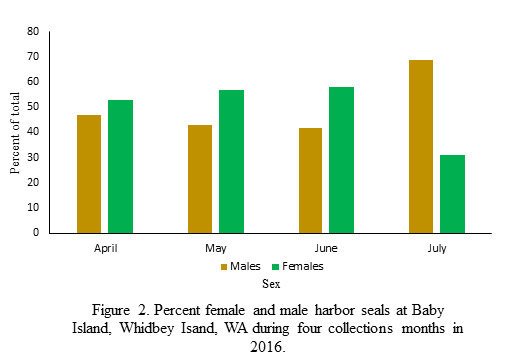

The highest number of successfully sexed scat were collected in May (Figure 1). Unfortunately, the sampling effort was not consistent across all collection months so this increase cannot be linked to variation in haul-out use. For the months of April, May, and June the ratio of females to males was approximately 1:1 (Figure 2). However, in the month of July that ratio shifts heavily towards females and is about 2.26:1 (Figure 2). I propose that the shift in female:male ratio in July is connected to the onset of pupping season in the region. Female harbor seals give birth on land and nurse their young for approximately 6 weeks (Jeffries et al. 2000). In the Whidbey Island Basin, the pupping season begins in earnest in July (Jeffries et al. 2000). During this time female harbor seals are more closely tied to haul-out sites, potentially skewing the female:male ratio. Testing this hypothesis is not the focus of my thesis but it is interesting food for thought!

References

- Jeffries, S.J., Gearin, P.J., Huber, H.R., Saul, D. L. & Pruett, D. A. (2000). Atlas of Seal and Sea Lion Haulout Sites in Washington. Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife, Wildlife Science Division, Olympia, WA. pp 150.

- Matejusová, I., Bland, F., Hall, A. J., Harris, R. N., Snow, M., Douglas, A. and Middlemas, S. J. 2013. Real-time PCR assays for the identification of harbor and gray seal species and sex: a molecular tool for ecology and management. Marine Mammal Science 29: 186-194.

- Rothstein, A.P. (2015). Non-invasive genetic tracking of harbor seals (Phoca vitulina). M.S. thesis, Western Washington University, Bellingham, WA.

Non-native salmon escape sparks debate on risk of fish farms

MacKenna Newmarch, undergraduate student

1 September 2017

On August 19th 2017, a sea pen holding Atlantic salmon (Salmo salar) near Cypress Island, Washington, imploded allowing hundreds of thousands of fish to escape. The cause of this event is still unknown, though the company responsible, Cooke Aquaculture, incorrectly blamed low tides leading up to the solar eclipse. Since that time, 141,576 of the 305,000 escaped have been recaptured as of August 29th (Department of Natural Resources).

With my research being focused on a native salmon species, the Nooksack stock of the Chum salmon (Oncorhynchus keta), now potentially at risk by a randomly introduced invasive population, it is certainly a cause for concern. For me, the debate on whether we should continue to invest in salmon fish farms is largely unresolved, as I see the pros and cons to both sides. This event reignited my interest in examining whether the potential catastrophe provided by a rupturing sea pen housing a potentially dangerous species or the possibility of farmed salmon interbreeding with wild populations truly outweighs the benefits of a more plentiful food source.

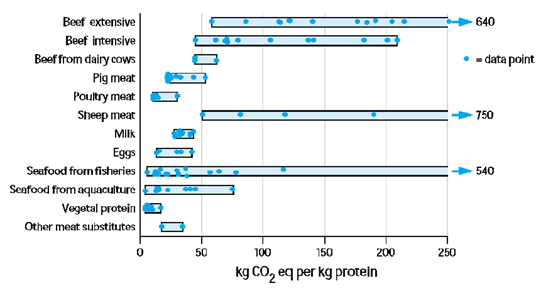

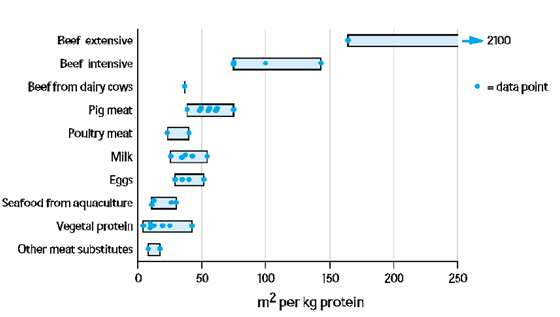

As a vegetarian, it can be all too easy for me and all those who do not eat fish to dismiss farming salmon since we lose nothing by removing that source of food, when the reality is that many people depend on salmon as an important source of healthy protein. Without the affordability of farmed salmon, consumers would instead turn to other animal protein options that tend to have a greater carbon footprint and take up more space, like red meat (see figures below)

.

.

Carbon footprint and area occupied relative to protein source. From Nijdam et al. (2012)

Atlantic salmon make up a large portion of farmed salmon worldwide. If not bred in Washington State, much of Atlantic salmon is shipped from Chile, not only resulting in a more expensive product, but making it less carbon friendly. The industry also provides great economic value to Washington, exceeding $40 million according to Washington State Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW). Being the only state on the West Coast of the U.S. where Atlantic salmon pens are legal, our waterways become very appealing for this particular type of aquaculture

It is difficult to overlook the positive impact these non-native salmon have, despite the risk to our endangered native stocks of competition, predation, disease transfer, hybridization, and colonization (WDFW). As Chris Wilke, executive director of Puget Soundkeeper Alliance said; “We do not want to deny anyone’s right to grow fish for profit to, you know, feed the world, but these operations can exist on shore. That’s the way we grow rainbow trout. That’s the way we grow tilapia. That’s the way we grow catfish and it can be done with salmon too.” However, companies like Icicle Seafoods (who also have Atlantic salmon pens in Washington State) claim there are no successful ways to farm salmon on land. Energy and operating costs skyrocket, as does their price tag, and the quality of taste and growth of the salmon decline. Icicle also claims salmon would not have the space they need in these inevitably crowded environments, which threatens animal welfare.

So, what do we do? Where can we find a happy medium?

While I imagined creating many hatcheries along the West Coast promoting wild salmon populations for consumption, like our hatchery at Whatcom Creek, would be a good alternative, it turns out that they are not the ideal species for farming. “Atlantic salmon are the most efficient at turning food into flesh” says Michael Rust, the science adviser for NOAA's office of aquaculture (Flatt, 2017). They tend to be more docile than the (truly) wild salmon, so choosing to farm wild species is unappealing to companies who want the most bang for their buck.

Seeing as how the main issue that arises from farming Atlantic salmon is the risk and apparent inevitability of the salmon escaping, it seems taking more preventative measures to keep them from doing so would be extremely useful. While we cannot say what caused the destruction, if backup nets surrounding the enclosures were used, it certainly might have helped. In the event that salmon do actually escape, as they have in the Salish Sea several times in past years (Amos et. al. 1999), there is luckily no record of them successfully establishing themselves. Farmed salmon are also not great at hunting, as they are accustomed to being fed, and have not developed qualities necessary to escape predators (Rust et. al. 2014).

Until the world is able to live on a purely vegetarian diet, I believe we have to make meat options that are more carbon friendly more appealing to the everyday consumer. While adding a stressor to an environment that already experiences great anthropogenic pressure cannot be a good thing, many of the issues provided by increased carbon dioxide levels provide arguably greater threats. We have to pick our poison.

Meanwhile, let’s hope our marine mammals can at least benefit from this food source – who knows, maybe Atlantic salmon turn out to be a new favorite of our Harbor Seals! We will certainly keep our eyes peeled at the creek.

References

- Amos, K. H. & Appleby, A. (1999) Atlantic Salmon in Washington State: A Fish Management Perspective. Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife.

- Commercial Net Pen Salmon Farming in Washington State. Icicle Seafoods.

- Cypress Island Atlantic Salmon Pen Break. Washington State Department of Natural Resources.

- Flatt, C. (2017, 29 August) Why Are Atlantic Salmon Being Farmed in The Northwest? National Public Radio.

- Nijdam, D., Rood, T. & Westhoek, H. (2012) The price of protein: review of land use and carbon footprints from life cycle assessments of animal food products and their substitutes. Food Policy 37: 760-770. DOI: 10.1016/j.foodpol.2012.08.002

- Rust, M. B. et. al. (2014) Environmental performance of marine net-pen aquaculture in the United States. Fisheries 39:508-524. DOI: 10.1080/03632415.2014.966818

- Washington Department of Fish and Wildlife (WDFW). Atlantic Salmon.

My experience in the marine mammal ecology lab

Raven Benko, undergraduate student

1 September 2017

As my time managing our lab’s Bellingham Bay harbor seal population study comes to a close (don’t worry, the project is still continuing without me, I’m just graduating soon), I decided I would use my last blog post as a way to reflect on my time on the project and share what I have learned. Working on this project has been a lot of fun and a lot of responsibility. Not only do I feel as though I have gained many useful skills that will make me more marketable in my future, I feel as though I have also made connections in the field that I can use to make my way in the world once I graduate! So, let’s see what I’ve learned!

First of all, I have of course learned a little but more about how science is done. This project was particularly interesting to join as a student researcher as it is a long-term study that was started long before my time. When I came on as undergraduate project manager, not only did I have to get quickly acquainted with the study site, subject, data, and methods, I also had to begin thinking about how we could improve the study while maintaining a methodology that allowed us to make comparisons with previous years’ data. An option was to simply keep everything the same a collect one more year of data on harbor seal abundance in a construction site. However, that would not make for a very interesting story and would not have utilized my time efficiently. About eight months after I began on the project, the log booms that the harbor seals we were studying had historically hauled out on were removed for construction purposes. This large disturbance event allowed us to make some interesting comparisons about what level of disturbance the seals would tolerate and what factors were actually keeping them in the study site despite large amounts of construction activity.

As my final project, I was able to analyze the data and see that during other large scale disturbance events near the haul-out site (i.e. building demolition, shoreline armoring, dredging) there was no significant difference in monthly average seal abundances as compared to our counts before the construction had begun. It was not until the log booms were permanently removed that we saw a significant decrease in monthly average seal abundances, suggesting that the harbor seals in the area tolerated a variety of construction-related disturbance as long as there was a relatively sheltered haul-out structure for them to utilize. This also pointed to possible habituation to construction disturbance and may suggest that harbor seals would return to the area in historic quantities if the log booms were replaced. I was able to present this data in the form of a poster at the Northwest Student Chapter for the Society of Marine Mammology held at the University of British Columbia as well as at Western Washington University’s Scholars Week in spring 2017. The experience of taking our data and seeing what I could make of it, creating a poster about my findings, and presenting at several venues was invaluable and allowed me to understand the scientific process a little more thoroughly.

Another skill that I learned while a project manager was how to properly lead a group of student researchers. It was one of my responsibilities to interview and select new team members which turned out to be one of my most rewarding jobs. I found out that I love working with a team of peers, coming up with solutions to problems that we faced, and mentoring students in the beginning of their undergraduate careers. This experience has made me consider going into a profession where I can mentor, teach, or interact with students and pass down the lessons that I have learned. I also learned what makes for a good application, interview, and candidate which I believe will help me with my own applications and interviews in the future!

It is difficult to put all of the lessons I have learned and skills I have gained from this experience into a single blog post. Other skills include time management, organization, creative and professional writing techniques, presentation skills, professionalism, and critical thinking. This experience has truly been one of a kind and I couldn’t have done it without the help of my team Virginia O’Callahan, Holden Miller, Alisa Aist, Logan Kuhn, and Mariah Kollasch as well as my mentor and our lab P.I., Alejandro Acevedo-Gutierrez. The other members of the marine mammal ecology lab were also amazing people to work and share my ideas with during our weekly meetings about the ever-changing world of science. I will look fondly back on my time as an undergraduate project manager for the marine mammal ecology lab, but I’m not done yet!

This next month, I will be passing on the torch to Alisa so she can bring one more year of the project to the world and community. It will be interesting to see her direction and ideas for the project. I will be graduating in December and spending my last quarter continuing my work with our graduate student, Madelyn Voelker, analyzing the diet of harbor seals in the San Juan region as well as working with Dr. Dietmar Schwarz on the desiccation resistance of snowberry and apple maggot flies. After that, I am out into the great unknown. I plan to get a little more experience in the field before I decide which graduate program I want to apply to. I’m sure everything I have learned in the marine mammal ecology lab will serve me well as I embark on the next adventure life has in store!

Signing off for the last time…

Raven