January 2017

Photo-identification: process and uses

Rachel Wachtendonk, undergraduate student

January 2017

When doing ecological or population-based studies, photo-identification can be a very useful tool. In our study site, Whatcom Creek, we take pictures from the surfacing events to use for photo-identification. Once we have identified the various individual harbor seals that visit Whatcom Creek we can use this data for many different types of data analysis. We can determine if the same seals are returning to the creek year after year, and if certain seals are more successful at catching salmon. We can also match the surfacing events to the behavior data to see if the behavior state of the seals change based on different environmental factors.

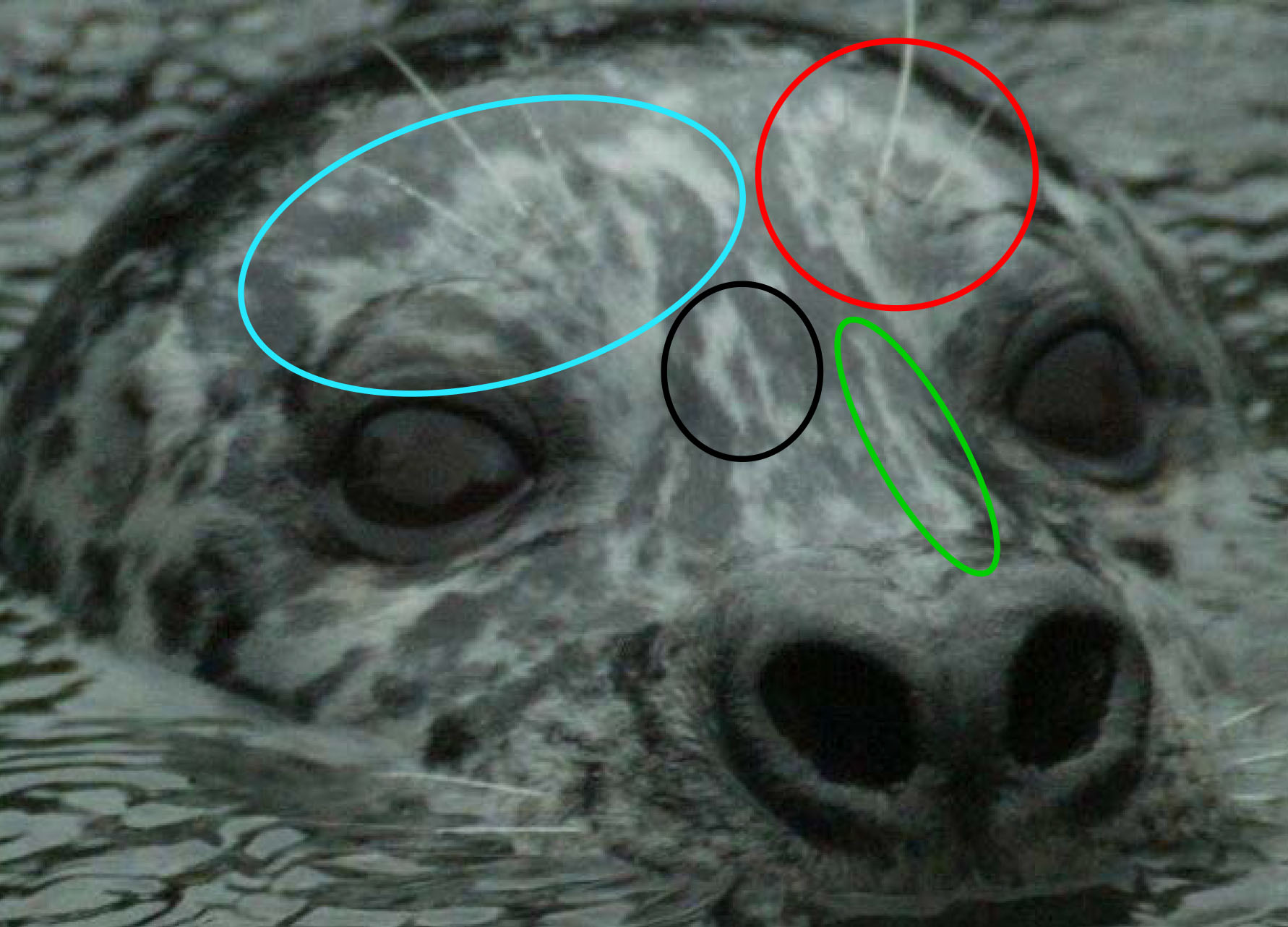

But photo identification is a very time-consuming and challenging process. Harbor seals have distinctive spotting patterns which can be used to determine the individual seals. The tried and true method of photo-identification is to do it by hand. You find a spot or cluster of spots that are easily identified on the seal. For example, the seal pictured below has a few good reference spots: the light half circle with a dark spot above the ear (pink) and the round spot with the dark center (yellow) will helpidentify this seal in other images with the same orientation. The straight line going upthe snout (green) and the rounded cluster of spots above the eye (red) will help not only with images with the same orientation, but front facing images as well.

Photo by Marine Mammal Ecology Lab.

The next photo is of the same seal, but with a different orientation. You can see the marks in red and green that are the same as the image above. The other marking on the snout (black) and the one above the eye (blue) will helpwith front facing images as well as right facing photos.

Photo by Marine Mammal Ecology Lab.

In the following photo you can see the blue and black markings above. Also the dark shape below the eye (purple) and next to the eye (orange) will help identify the seal in this orientation.

Photo by Marine Mammal Ecology Lab.

Using these markings we can compare them to future images to see if this seal returns to the creek. Doing this method is very time consuming so many computer programs have been developed to assist with photo identification. But still these programs need a lot of human helpto make matches so it still is a time-heavy process.

Continuing the seal search

Raven Benko, undergraduate student

January 2017

As monitoring of the Bellingham bay harbor seal population continues, we have been searching for potential new haul-out sites in the area that may be used as a replacement for the log booms in the Log Pond (for those new to the blog, check out my January 2016 post for a brief overview of the project here). With the log booms removed, we are curious to see what happens to the harbor seals in the area. Will they leave the industrial area altogether even though it is a prime hunting ground during salmon season? Or, will the seals search out a new haul-out habitat nearby that could provide them the same comforts as the Log Pond? Is there even such a place? These are the questions we have been trying to answer in the last few months of monitoring.

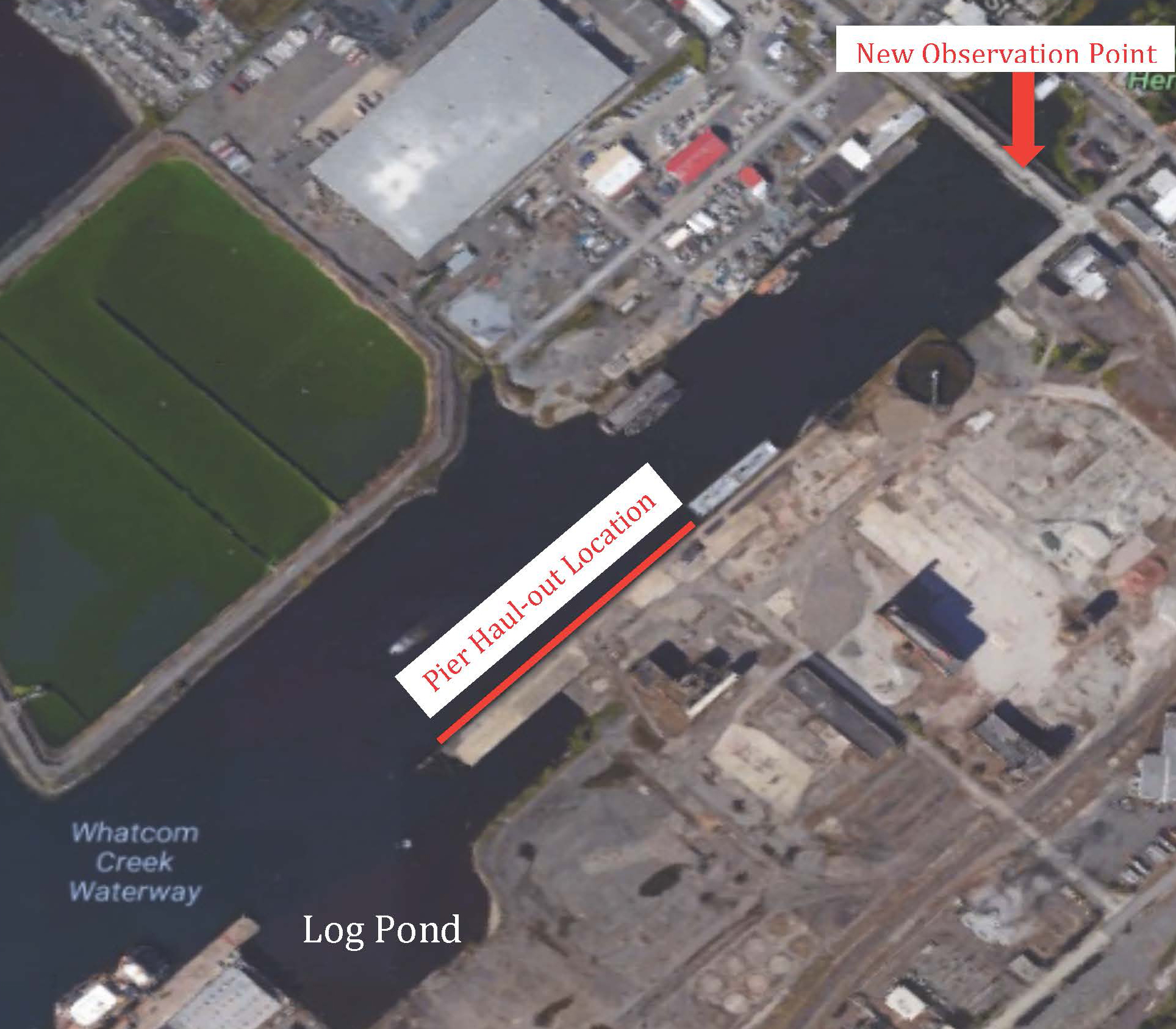

Our first hypothesized haul-out site is located along the pier bordering the Whatcom Waterway, very close to the Log Pond (see mapbelow). We were tipped off by some Port of Bellingham workers who mentioned that they have seen seals hauled out on the log booms that are floating along the pier. Unfortunately, these booms have been in place for many years but have never been monitored by the Marine Mammal Ecology Lab, so it may be possible that seals have been on the log booms surrounding the pier this whole time. Our initial observations throughout the past summer and fall have not indicated that these log booms are highly frequented by harbor seals, with observations showing a maximum of two harbor seals on the booms on rare occasions. These log booms may be less popular due to the loud and frequent traffic that crosses the bridge over the Whatcom Waterway on West Holly Street. The log booms are also in the shade until about 1:00pm, but we have had rare sightings of seals using this potential haul-out sight even after 1:00pm.

First potential new haul-out site. Modified from Google maps.

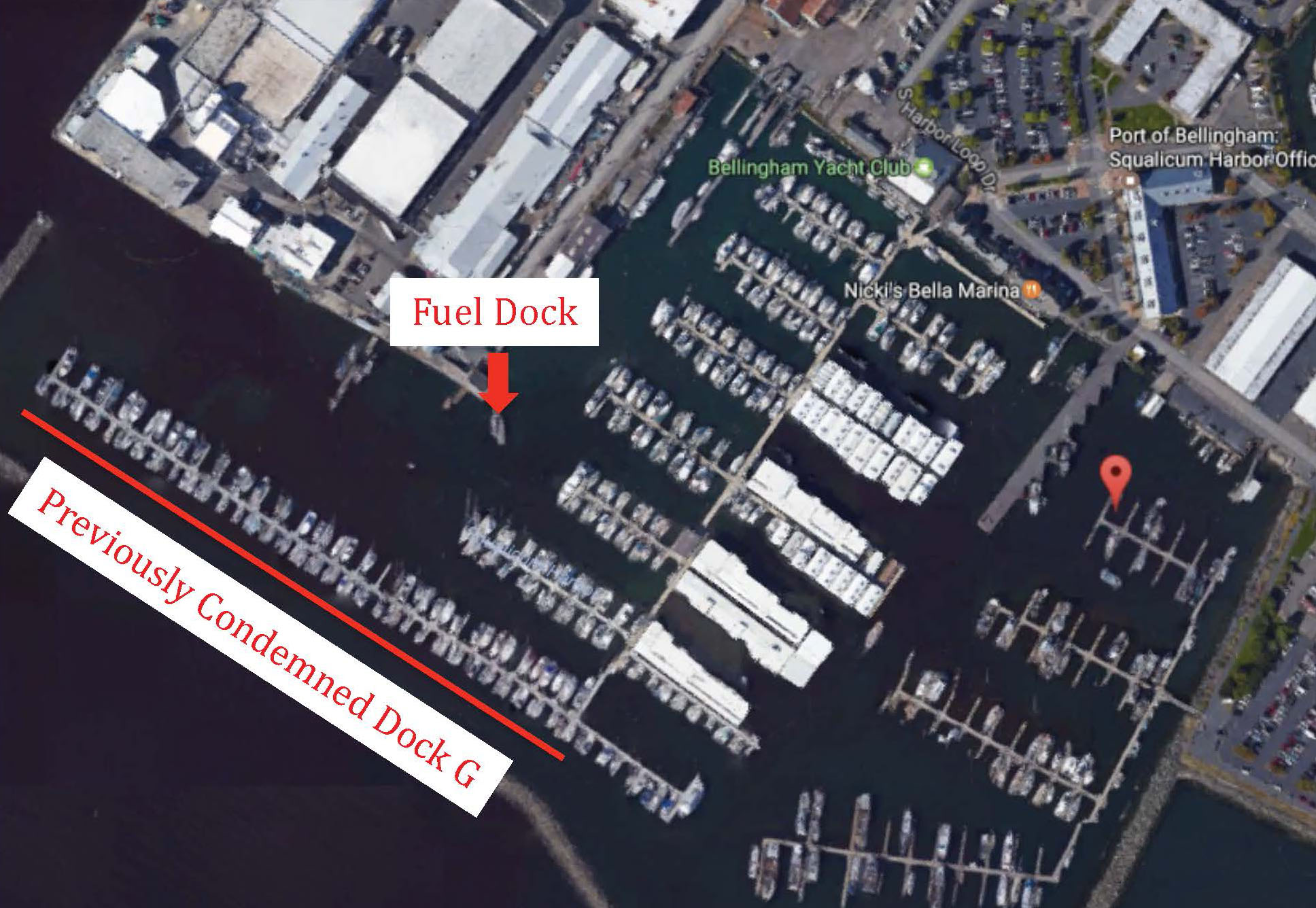

The next potential haul-out site replacement we have been looking into is located in Squalicum Harbor on the fuel dock. Seals have been historically known to haul-out at this location. In fact, one of our former lab members, Sara Cendejas-Zarelli, studied a groupof seals at this haul-out site between 2008 and 2009! (You can read her paper here.) However, we have not had much luck finding any seals at the fuel dock these days. Upon further investigation, I learned from a harbor representative that a portion of the harbor (dock G to be specific) may have been condemned at the time that Sara was observing the seals at the fuel dock (see mapbelow). The condemned area would have been right near the fuel dock and may have made the area a more comfortable haul-out sight for the seals due to decreased boat and pedestrian traffic. As of late, neither my team nor those who work at the harbor have seen evidence of seals using the fuel dock as a haul-out site. We may have to abandon this area as a potential replacement for the Log Pond.

Second potential new haul-out site. Modified from Google maps.

The last potential haul-out site replacement was a suggestion from a Squalicum Harbor representative and is located at a different fuel dock across from the Coast Guard Station at the Squalicum Harbor. I have been monitoring this spot for a week or so and so far haven’t seen any seals hauled out on the dock or the log booms that are surrounding a small pier there, but I have seen several seals swimming in the small channel.

Third potential new haul-out site. Modified from Google maps.

We will continue monitoring this site throughout spring and summer to determine if it is a viable alternative for harbor seal haul-out! Happy holidays, more to come next month.

Why not be a generalist?

Madelyn Voelker, graduate student

January 2017

So far winter break has been pretty good to me and allowed me some additional time to read literature for my thesis proposal. Some of the literature I recently read piqued my interest in finding a biological theory for the occurrence of individual specialization. Individual specialization occurs when an individual utilizes a subset of the resources their population uses (Bolnick et al. 2003). Populations of harbor seals, as a whole, have been repeatedly documented as consuming a broad range of prey types. Thus, harbor seals are considered by many to be a generalist species. So, I asked, what would be beneficial about only utilizing a subset of prey species available to an entire population? I initially assumed specializing would put an individual at a disadvantage. However, there are numerous documented cases (93) of individual specialization across a wide range of taxa (Bolnick et al. 2003). This broad range and large number of documented cases suggests there must be some advantage to being a specialist. Thus, the question, why not be a generalist? In one word – trade-offs. Due to trade-offs, being a generalist doesn’t always give an advantage.

Put succinctly, the theory is as follows: if specific techniques are best suited for capturing specific prey types, and an individual has a limited capacity for effectively learning and using multiple techniques, then that individual will be limited in the number of prey types it utilizes (Sutherland and Ens 1987, Hoelzel et al. 1989, Kato et al. 2000). Basically, an individual might have more optimized foraging when specializing on relatively fewer prey items. A couple examples of documented trade-offs are jaw-closing strength versus speed (Wainwright and Richard 1995) and foraging speed versus maneuverability (Ehlinger 1990). These two examples jumped out at me because I immediately started thinking about how these trade-offs would apply to harbor seals.

It has been wonderful to have the opportunity to read more academic papers these last couple weeks, but as usually happens when I dive into the literature, I have more questions now than when I started. In conclusion, I am not yet sure how all this information might contribute to my thesis, but it sure is interesting food for thought!

Happy New Year,

Madelyn

References

- Bolnick DI et al. (2003) The ecology of individuals: incidence and implications of individual specialization. The American Naturalist 161:1-28.

- Ehlinger TJ (1990) Habitat Choice and Phenotype-limited Feeding Efficiency in Bluegill: Individual Differences and Trophic Polymorphism. Ecology 71:886–896.

- Hoelzel AR, Dorsey EM, Stern SJ (1989) The Foraging Specialization of Individual Minke Whales. Animal Behavior 38:786-794.

- Kato A et al. (2000) Variation in Foraging and Parental Behavior of King Cormorants. The Auk 117(3):718-730.

- Sutherland WJ and Ens BJ (1987) The Criteria Determining the Selection of Mussels Mytilus edulis by Oystercatchers Haematopus ostralegus. Behaviour 103:187-202.

- Wainwright PC, and Richard BA (1995) Predicting Patterns of Prey Use From Morphology of Fishes. Environmental Biology of Fishes 44:97–113.